This morning I was informed that one of my tweets had fallen afoul of the Twitter “rules against abuse and harassment.” The tweet in question, which I was forced to delete as a condition of beginning the countdown to unlock my account, read:

bizarre and quixotic attempts to distinguish the TSQ cover from any number of other feminist evocations of hyper feminine violence aside, i have a question: would we generally understand this meme as itself a feminist image? I can imagine the argument either way.

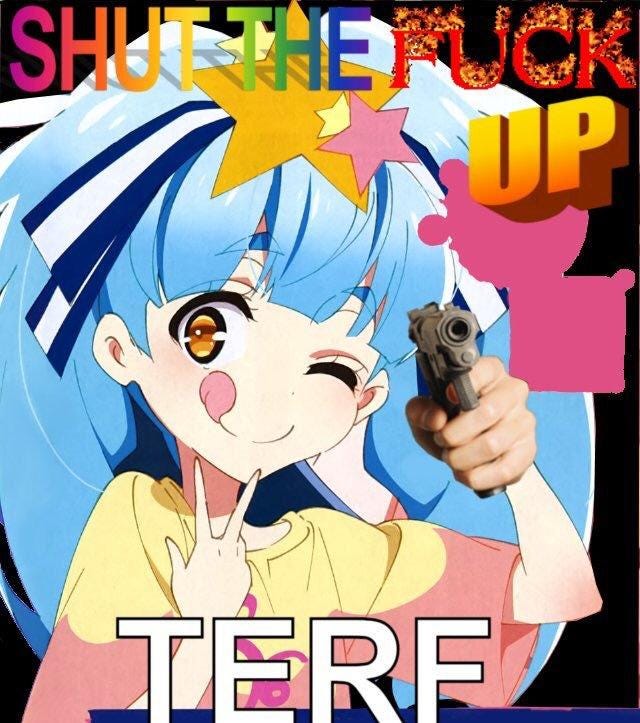

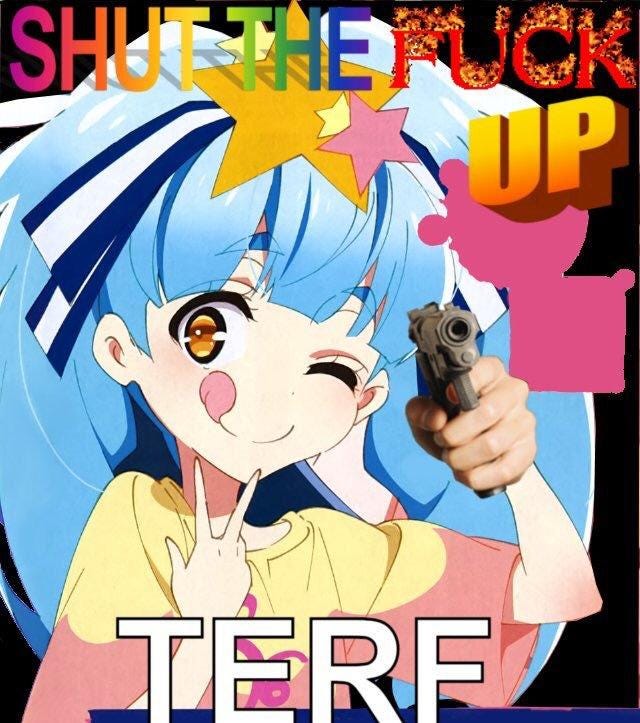

The image in question was this one:

Which says “Shut the fuck up TERF,” with a picture of an anime girl apparently holding a gun. The image, of course, could conceivably be conceived as abuse or harassment. But a scholar inviting a discussion of the meaning of that image could not.

Let’s call this what it is: an assault on academic freedom.

Honestly, I’m on holiday this week so quite happy to have an enforce break from Twitter. But life being what it is, I’ll walk through the discussion we could have had.

A couple of days ago, a number of gender critical activists found the cover of the new cover of Transgender Studies Quarterly, and implied that it contained an implicit threat of violence against them. The rush appeared to start with Julie Bindel, an outspoken opponent of civil rights for trans people.

The image in question was a photograph from an installation by the Taiwanese cis feminist artist Shu Lea Cheang, entitled 3x3x6. The issue’s editors, Eliza Steinbock and Yv Nay, both respected feminist scholars, chose this image for the cover, and explained their reasoning in the issue’s introductory essay:

With the notion of enclosures and policing of deviance in mind, we will close with a short analysis of the cover image, from the documentation portfolio shot by trans visual artist and filmmaker Johanna Jackie Baier of queer digital artist and filmmaker Shu Lea Cheang’s (2019) 3x3x6 installation for the Taiwanese Pavilion of the Fifty-Eighth Venice Biennale. The title 3x3x6 refers to the industrial stan- dard of prison architecture that calls for cells that are three meters square and are monitored by six cameras. Curated by the trans Spanish philosopher Paul B. Preciado, Cheang’s installation draws attention to the (dis)continuity of disci- plining, surveilling, and imprisoning from 1755 until today, with contemporary queer and trans performers reprising roles of ten historical and current cases of imprisoned gender and sexual dissidents: Casanova (Italy), de Sade (France), Foucault (in Poland), as well as cases from Germany, the United States, the United Kingdom, Taiwan, Zimbabwe, and South Africa. Their fictionalized portraits include composite prisoners as well, like D X, a transgender man who in the 2010s was imprisoned for the crime of “rape by deception” for not revealing his gender status. The viewers’ interaction with their narrative storylines work to expose the outer limits of cultural norms that are carved with the hard line of criminality. The pavilion makes use of the Palazzo delle Prigioni, a Venetian prison from the sixteenth century in operation until 1922, by reimagining a panopticon structure as a space now overlaid with three-dimensional facial recognition, artificial intelligence, and internet tools of surveillance and control. The public program took place in a former psychiatric hospital located on an isolated island to highlight the procedure of removal and segregated containment central to both forms of incarceration, in a prison or asylum. The so-called treatment of “mental illness” conducted there included early on “a vast array of gender-, sexual-, and class-excluded subjects such as ‘repugnant poor people wandering the city,’ ‘unruly women,’ ‘hysterics,’ and ‘deviants’” (Venice Biennale 2019).

In other words, while Bindel saw in the image a threat aimed directly against anti-trans activists like herself, Steinbock and Ny saw three glitzy feminist activists confronting the punitive institutions of prison and mental hospital, asserting their own freedom, and collectively articulating the aesthetic promise of militant feminist politics.

I have to say, I found Steinbock and Ny’s reading more persuasive than Bindel’s, and not least because, unlike her, they had actually done some research on the image. I think many people––probably most––who saw the Cheang photograph would see in it a suite of visual references to other kinds of arty femme militancy, that might have included:

Riot Grrl bands like Bikini Kill…

lesbian punk bands like Tribe 8…

Chicks on Speed…

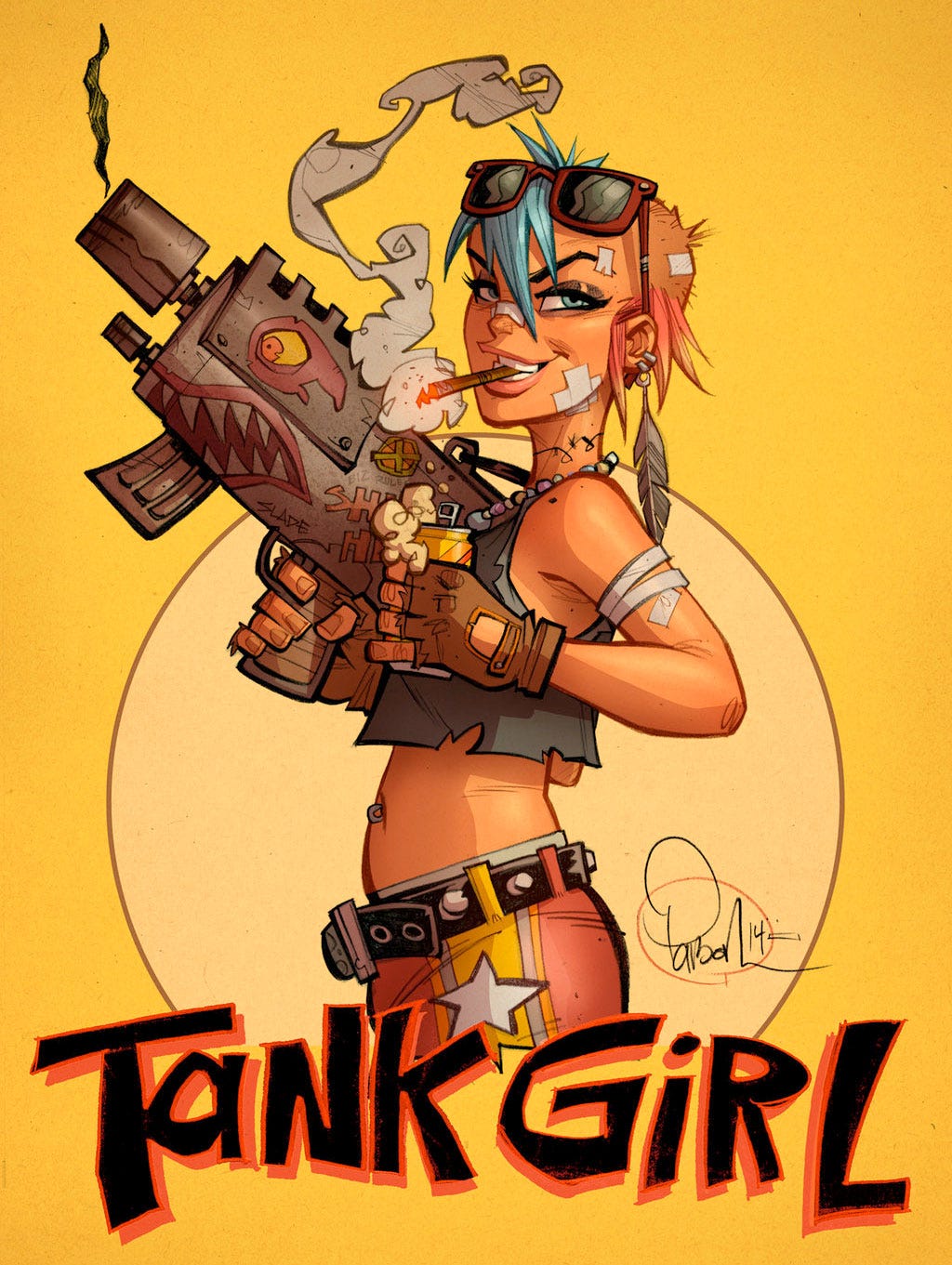

Tank Girl…

Pussy Riot…

Harley Quinn…

…and millions more. The anti-trans activists sneered at the phrase “hyperfeminized violence,” but it identifies something quite easy to recognize and fairly ubiquitous.

Of course, anyone would be welcome to argue that this imagery is not feminist––especially Harley Quinn and Tank Girl, characters created by male writers. But of course the question is worth asking. Do we imagine these girly gun-toters as feminists, or as ciphers of patriarchal violence? I can’t imagine how one could possibly teach a class on feminist visual culture without asking that question often.

Of course, none of those were the image that Twitter has censured, which again, was this:

Here we have an image that is strikingly similar to the others in any number of respects: cute, cartoonish girl, check; gun-as-dick pointed in your face, check; titillating friction between femininity and violence, check. On a different day, or for a different purpose, I would be minded to argue that the other images-–from riot grrl on down––traffic with the titillating spectacle of the chick-with-a-dick, and to that extent depend upon what the feminist scholar Emma Heaney has called “the trans feminine allegory.” But for now, all I want to argue is that this image obviously has a certain amount in common with the others, and that therefore––given that it is avowedly a feminist image––it behooves feminists to take that claim seriously.

By shutting that conversation down, Twitter has decided that it already knows what feminist imagery is, and what kind of conversations one should have about it. The spectacle of watching activists who believe themselves to be feminists attempt to limit the kinds of conversations feminists can have about imagery and iconography is depressing enough. But it goes without saying that a social media platform has absolutely no use if it prohibits conversations of this kind.

My gender-critical friend, with whom I disagree about most things trans, was good enough to tweet about this. I want to thank her.

I’m quite sure that those who complained about my tweet will take it as evidence that I am an abusive harasser. I’m not. Meanwhile, I’m hoping someone might be so good as to alert those proud defenders of free speech who have made their fortunes out of being canceled. You know their names––we all know their fucking names.

I am a public educator. Part of my job is to initiate, moderate, and summarize difficult conversations. This is a disgrace. Twitter should reinstate my account immediately, although I hope they don’t because, as I say––I really want to be offline and on holiday for the next week. But that’s not to say that others shouldn’t be concerned about this.

∿