I’m beginning to worry that my old system for classifying dystopian franchises has had its day, and I’ve not even published it yet. So I’m rushing this out into the world just at the moment when I’ve really lost faith in it. The claim is this: that while we refer to “dystopian fiction” as a relatively singular framework, in reality it is two genres, with surprisingly little in common, which project and codify radically different articulations of the future, freedom, power, love, etc. There are rough dystopias and smooth dystopias. At the extreme end, rough dystopias depict worlds in which liberal institutions have collapsed entirely, and have been replaced by violent and unpredictable resource competition: Mad Max: Fury Road, for example. At the other extreme, smooth dystopias depict worlds in which liberal institutions have even more fully enveloped the world, displacing all personal and communal claims to autonomy: I guess, off the top of my head, The Circle is a decent example.

Of course it goes without saying that these are extreme cases and there are plenty of mixtures. Blade Runner, for example, depicts wealthy tech plutocrats and indistinguishable biological clones (common “smooth” tropes), while mostly taking place in disregulated spaces of economic exchange (typically the backdrops of rough dystopias). This turns out not to be a problem. Rough dystopias (I think Blade Runner qualifies) often depict some kind of smooth world—the difference is that in an actual smooth dystopias power, and plot, flows seamlessly from smoothness into the world, whereas in a rough dystopia, smoothness is cordoned off from what really matters, what is really happening. One of the greatest dystopian movies of the century, Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men, is at the extreme end of the rough spectrum, but still has that one scene with Danny Huston in a big white art space—smooth as you like. It’s just that the plutocrat’s power is limited, and the real events of the movie are effectuated by massy gangs of bodies—hustling inside internment camps, bombarding Bexhill-on-Sea, or emerging screaming from the woods.

I have a theory as to why rough dystopias often depict smoothness, but the smooth dystopias don’t usually depict roughness. Take The Circle again—not a great movie by any means, but a useful example. Here we have a world in which a liberal corporation, played by America’s dad, Tom Hanks, has absorbed a number of different economic sectors, and is attempting with some success to smoothen the world. Positioned as the unsmoothable hold-out is our protagonist Emma Watson’s rural poor family, especially her father who has MS. (Disability as indigence, as resistance to modernization—a Dickensian trope.) The problem is that the scenes with the parents are bathed in the same beautiful NorCal twinkle as the rest of the movie, and, in aesthetic terms, do nothing the arrest the parade of lovely, vapid Silicon Valley visual branding about which the movie is encouraging us to maintain a degree of skepticism, albeit a rather acute one.

So the theory is this: rough dystopias are developed from the Western genre, and as such concern themselves with frontiers, social hierarchies, and their fragmentation in the face of real human encounters. Star Wars is not usually thought of as a dystopia, though it is widely understood as a kind of Western. But the early movies have a certain amount in common with Blade Runner et al, and furnish a moral aesthetics in defiantly rough and smooth terms. Han Solo’s stubble: rough, good. Darth Vader’s helmet: smooth, bad. Luke Skywalker, with his blue eyes and boy band bob, definitely has a smoothness about him, which might connote an infantilized innocence, but also (viz his paternity) a kind of suspicious incipient thirst for power. Rough dystopias may hate roughness, but they hate smoothness even more.

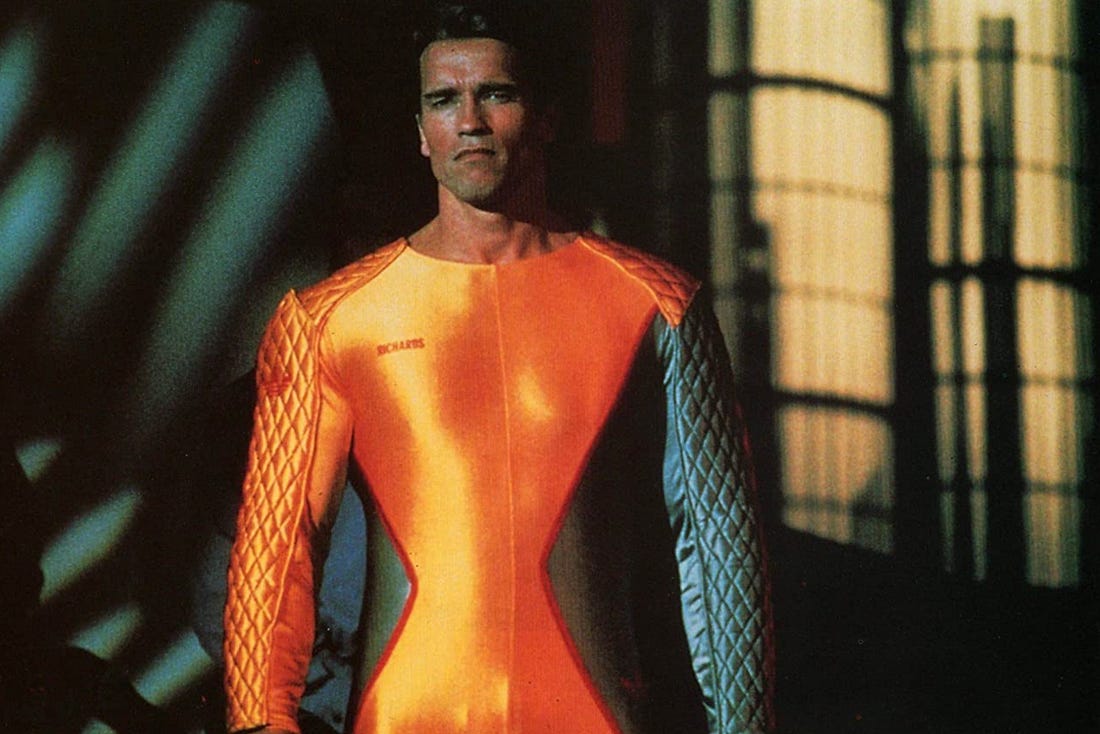

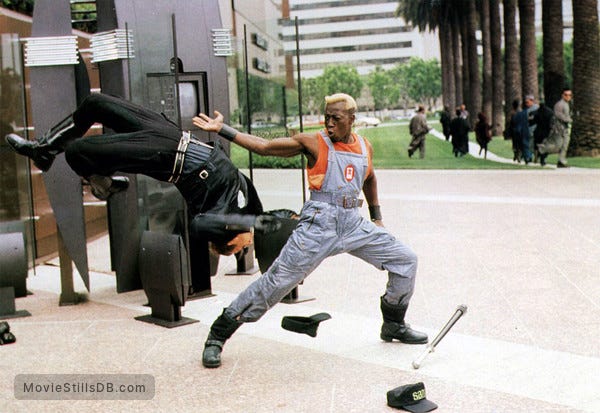

Smooth dystopias hate smoothness, and are okay with roughness in small doses. I’m fairly sure I’m not the only person who wishes that the Hunger Games movies contained less of the fighting, and more of the posing in glamorous rococo outfits. But the movie I wanted to watch, I suppose, was The Running Man. Here, the glamminess of the smooth world extends outwards with plot and power. Arnold Schwarzenegger (a smooth man in almost every sense) is sent into an underground zone to fight garishly—or, depending on your view, glamorously—appareled ruffians, for the amusement of an audience watching on tv. Demolition Man is an even better example: supposedly a smooth dystopia being disrupted by two rough men, in fact both Wesley Snipes and Sylvester Stallone look utterly gorgeous in their brightly colored and immaculately tailored costumes. Even the underground “Scraps” seem well dressed, and are led by a man with an extravagantly smooth name: “Edgar Friendly.”

So if rough dystopias come from the Western, smooth dystopias come from sci-fi fiction, right? Not exactly. Their provenance is more complicated and contested. Certainly Philip K. Dick and Harlan Ellison are part of it, and their shared sense of fiction as the narrativization of a conceptual premise structures more plots than the movies adapted from their works. And in some ways, smooth dystopias share those authors’ kneejerk concern about the putatively feminizing effects of capital—Demolition Man is a wonderful movie, but in political terms utterly reactionary; and think of the unsexable and wobbly flesh-spheres that drift around the space ship in Wall-E. These tropes are achingly familiar from mid-C20 science fiction too, and one can trace them back to the Eloi in H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine, though Wells’ figuration of class and gender as mutually-constituting and mutually-undoing categories is more complex than most of its revisions.

Meanwhile George Orwell’s 1984, a smooth dystopia, is a far weirder book than most of its advocates or critics acknowledge, with few obvious precursors or comparators. Though it has elements of Victorian horror and science-fiction, much of the novel as a whole consists of political speculation, with the narrator flipping between plot and theory. To a Victorian reader, Orwell’s work might have looked like a Menippean satire, to use the term that Northrop Frye anachronistically gave the genre. A strange composite of encyclopedia and novel, the Menippean satires narrated the business of knowledge-making (of writing philosophy, for example, in Thomas Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus) as an essentially silly, incomplete kind of project. Edward Casaubon in Middlemarch is a figure from Menippean satire, drawn into a realist novel. These novels, like 1984, flip between grandiose theory and realist narrative, grounding a philosopher’s airy thoughts in the soil of his lived existence, with all its petty inadequacies and limitations. The genre often had an aspect that, while we might not recognize it as strictly dystopian, was similarly anthropological, in that it narrated the rules of a given social environment: Gulliver’s Travels, to take the most famous example, is part Menippean satire and part travelogue.

Which brings me to my recent crisis of faith in this division, which was brought about by the new Dune adaptation, directed by Denis Villeneuve. I’m not really the target market for either Dune or Villeneuve; I don’t like the sadistic dynamics of “hard science fiction” any more than I like hard science, and Villeneuve’s movies all seem determined to be very boring and drawn out. Although I did enjoy Rated R for Nudity as a kind of cheap conceptual gesture. But the Villeneuve movie is hard to place on the smooth—rough continuum because it smoothens out a visual-material element that, in many rough dystopias, stands for roughness itself: sand. In Mad Max: Fury Road, dust and sand are the rough matter of the universe, through which our heroes must travel in search of its logical and aesthetic opposite: water. But in Villeneuve’s Dune, sand itself is visually and materially water-like, rippling and expanding over space. So the smoothness of Dune is the same as its roughness—hence my conundrum.

What I think this conundrum makes available, though, is a new way to think about Orientalism as a cinematic phenomenon. I don’t know what Frank Herbert was thinking of when he made his spice-users’ eyes turn a preternatural blue, but surely anyone who watches Villeneuve’s movie is returned to Peter O’Toole’s performance in Lawrence of Arabia. David Lean’s movie is painful and disturbing to watch on account of Alec Guinness’s and Anthony Quinn’s brownface roles. I do want, though, to note that as a visual signifier, O’Toole’s whiteness is rendered monstrous and alien by Lean’s camera—a depiction of whiteness as surrealism. Whether or not mid-century British Orientalist movies of the Merchant-Ivory type might be, more broadly, a useful framework for considering smooth dystopias, I’m not sure—though one can certain conceive of political parallels between the official culture of the British state in the period of decolonization, and the collapse of the American empire in the present moment. But more to be thought about, anyway.

∿